The tightening of real-world Formula 1 testing allowances has amplified the importance of simulator work. Teams now only have three days of pre-season testing available, while the number of CFD items and wind tunnel sessions they can do is allocated on a sliding scale that gives the lower-placed teams more resource to improve. Driver-in-the-loop simulators have been used by F1 teams for decades now, but their development is ongoing. As real-world testing has reduced, so the simulator has assumed a greater role in assessing vehicle dynamics. It is an indispensable tool for getting the car ready for an event and trying out potential upgrades.

Central to simulator testing is the simulator driver, who is typically a professional racer in their own right. Despite not being regular faces at grand prix events, they have a significant part to play in what transpires at the track. So, what does the life of an F1 simulator driver entail? We asked the Aston Martin F1 team’s Nick Yelloly, who has been virtually testing F1 cars for a decade, to find out.

How much time does the job demand?

Yelloly has been an F1 simulator driver since 2014, working for three iterations of the same team lineage: Force India, Racing Point and Aston Martin. Seven or eight years ago, he would carry out more than 70 days a year, although the number has reduced slightly since.

‘When I was racing in Carrera Cup or Supercup in Germany, I had much more spare time for it than I do nowadays,’ says the Brit. ‘Nowadays I’ll do 40 to 50 days a year.’

That is still a lot when you consider that Yelloly is also a BMW factory driver, this year competing in the nine-round IMSA SportsCar Championship and various high-profile GT races. That leads to around 20 days per year at the BMW M Motorsport simulator in Munich, in addition to track testing responsibilities. When everything is put together, it is rare for him to have more than two or three days at home during the European racing season.

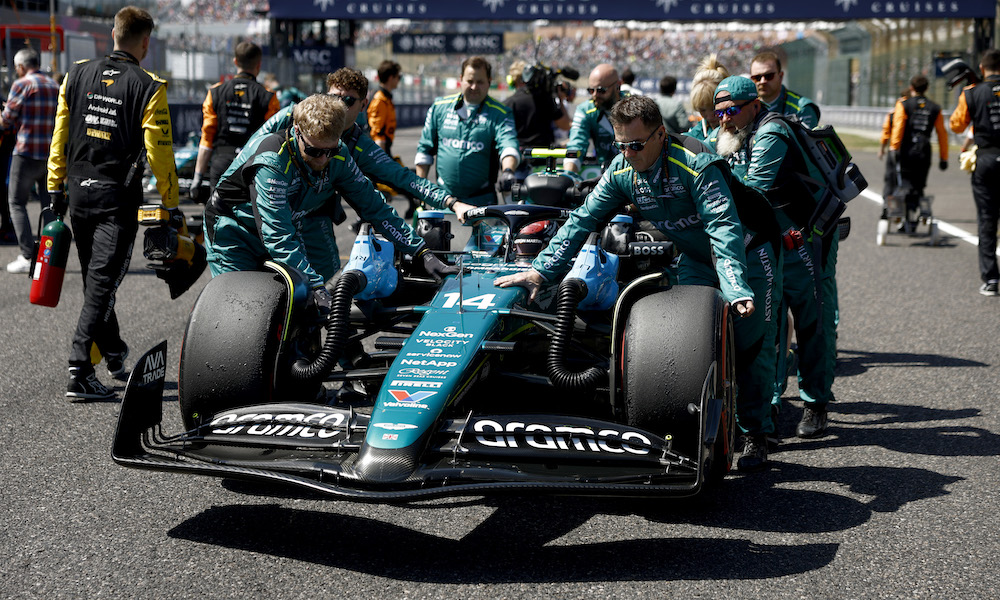

Yelloly’s racing programme with BMW has priority over his F1 simulator role, but he still needs to be flexible in case Aston Martin gives him a late call-up. The F1 team has several simulator drivers to choose from in addition to main drivers Fernando Alonso and Lance Stroll, such as reserve drivers Felipe Drugovich and Stoffel Vandoorne, or Aston Martin F1 junior Jak Crawford. This means there is some flexibility depending on schedules.

‘I am very flexible when I’m at home and will, at the drop of the hat, be able to go into the simulator and test things,’ says Yelloly. ‘If I’m free on a race weekend, I’ll do race support. For Hungary, we had a few new parts, and I was there until almost 2am. That tends to happen when we have new parts, because we need to extend test sessions more often. Generally, I’ll try to fit in one or two sessions a week.’

What does a simulator test consist of?

No two simulator sessions are the same, but there are certain types of session that reoccur during an F1 season.

‘It’s very dependent,’ says Yelloly. ‘You’ll have typical car performance days, sometimes you’ll have tyre development days, purely for correlation. Other times you’ll be doing pre-event work to get the basic set-ups ironed out for the race drivers before they come in. So, it’s broken up into three or four types of session.’

A standard car performance engineering session will focus on trying out new parts that have been modelled for the car. If they work as intended or bring lap time gains in the simulator, they are taken through into production.

‘Typically, it will be about trying new parts that they create in their software and modelling before we go and put them in the wind tunnel, or even CFD, to see if directionally that is correct or not,’ says Yelloly. ‘We can see if it’s bringing the tools or drivability that we may have been lacking, and creating load in the areas that we need. In F1, you need as much load as you can get without the drag. It’s quite a fine trade-off, and some configurations work better at some tracks than others. A lot of different aero and ride height scans are done between races, depending on track grip level and downforce expectations.’

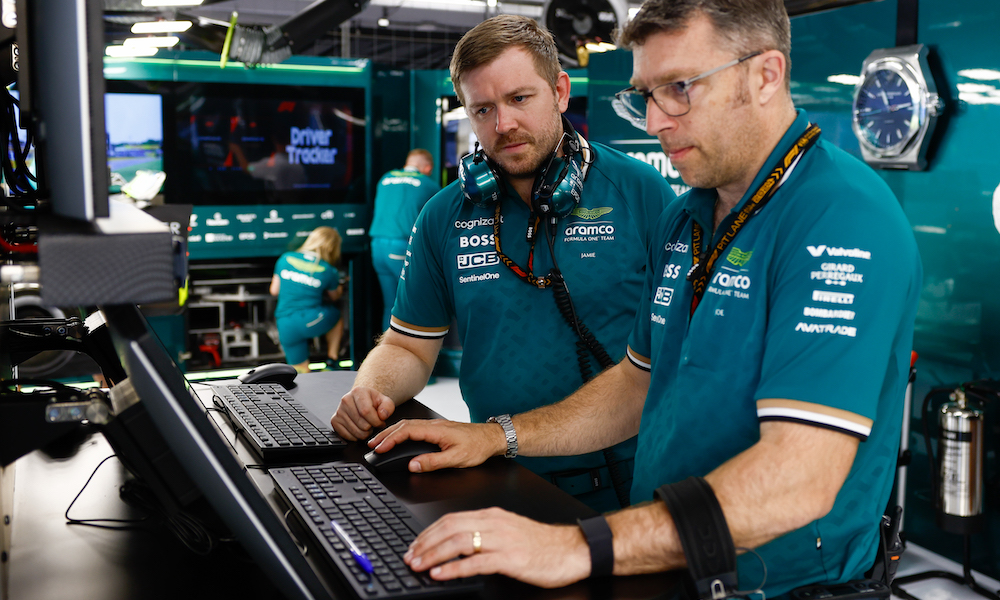

Aston Martin has a core team running the simulator, supported by a larger group of staff in the performance engineering department who can request items that can be tested and signed off before going onto the real car.

How does a sim driver contribute on race weekends?

The personnel at the track constitute only a portion of an F1 team’s staff count during an F1 grand prix. An army of engineers will be watching along at the factory, processing data and returning their findings. There will also be a simulator team in constant communication with the track squad, trying out set-up options that can’t be completed in the limited practice time available.

These race weekend simulator sessions are more intense than your standard engineering or tyre runs, for there is the added pressure of an event schedule to follow. Unsociable working areas can be expected for those at base, especially if it’s a flyaway race in a remote time zone.

‘We will do some pre-emptive set-up work to predict what they may ask for at the track,’ says Yelloly. ‘Sometimes, it isn’t the direction they want to go, but it could give them extra information on ways not to go for Free Practice 2. The main running that we try and dial in, at least for performance, will be one of the first couple of runs in FP2, because that’s when most teams tend to do their performance running.

‘We’ll start working on correlation, making sure grip levels are correct, and ride height and downforce levels are aligned. Once we’ve done that, we will listen in to debriefs, driver comments and engineer thoughts. There are so many different departments in Formula 1 that it’s quite a sizeable debrief length. As that’s happening, we will start to get test requests from the track. I like to think of it as them using us as an extended test session, for stuff they couldn’t get done in FP2 or ideas they have. Each direction they would like to try, they will send to us, and we give our feedback on yes or no, in terms of balance, feeling, drivability, general lap time consistency, and whether it’s more of a qualifying set-up or race style.’

The number of requests sent to the simulator team sometimes enters double digits across the two Aston Martin AMR24s. These can cover a wide range of topics spanning aerodynamics and mechanical matters. After testing an item or set-up option, the simulator team will relay their findings to the track team.

‘At that point, they either say it’s fine, or they can send more options if they are looking into more specific areas,’ says Yelloly, who acknowledges that pressure is high on the simulator team in these scenarios.

‘It can be quite tough,’ he adds. ‘We are structured in time limits, as to when they get their test requests across. After that, we usually don’t get out of the simulator until we’re done. At Hungary, it was three or four hours constantly doing laps. No matter what time it gets to, you’re going to struggle! Luckily the 24-hour race weekends that I’ve done plenty of seem to help with that.’

As professional racers, all simulator drivers are physically fit, but that doesn’t mean it’s not tough.

‘In a simulator you haven’t got adrenaline, which keeps you going in a racecar,’ notes Yelloly. ‘So you have to just be able to run on fumes, which you do at the end of a 24-hour race. I actually think my simulator work in the early days probably helped me with my endurance career, to start with. And then it’s helped full circle.’

Does a sim driver need a particular driving style?

Adaptability is the key word. F1 race drivers usually conduct several hours of simulator testing to prepare for a grand prix, yet there is still a need for dedicated sim drivers to go through the full mountain of items that a team needs to test. Simulator drivers must be able to mimic the driving style of the race drivers, to ensure their findings about a particular part or set-up will correlate with the real-world experience. If they can’t mimic those very detailed, individual actions, there is a danger their feedback could lead the trackside engineers down the wrong path.

‘It’s something that I learnt to do quite early on,’ says Yelloly. ‘Even the different gear usages: some people may attack the corners more and not worry about the exit much, and vice versa. Also, different lines and corner radii that each driver takes, I have to adapt to them. How I do it, is I go about my normal driving, and then I’ll ask if this is the correct [approach] to Alonso or Stroll. [The engineer] will give me feedback – “you need to carry in more speed or turn in a bit later” – and I’ll be able to fix it and mimic what they were doing. When you first start copying someone else, it’s a bit unusual and different. But now I’m at the stage where it’s relatively comfortable. Having worked with them for a few years, you know how to go about it.’

Do they ever get to drive a real F1 car?

Yes, and Yelloly has done. In fact, it’s necessary for the driver’s understanding between what is being experienced at the track, and what he feels during his many hours in the sim. This is especially important when F1 goes through technical regulation overhauls, as it did between the 2021 and 2022 seasons and will do again in 2026.

‘[A real-world test] usually tends to occur once there’s been a rule change,’ says Yelloly. ‘The first time I drove was in 2016, then it was 2019 when we had the bigger tyres and more downforce. And again, a few weeks ago in a PR day, they had me driving the ground effect car, just to have an idea of how it feels inside the cockpit and how it reacts. We also have bigger rims now than when I last drove an F1 car.’

How accurate are current F1 simulators?

The lack of real-world F1 testing nowadays has placed heavy emphasis on teams purchasing and developing the most accurate simulator possible. It is one of those unseen battlegrounds away from the track: investing in simulators is worth it because a better simulator should give more precise feedback on car characteristics that translate to good engineering decisions.

The term ‘latency’ is often used to describe simulator performance. This is the delay between something happening in the virtual environment and the driver being able to recognise that it is happening. Top-of-the-range simulators today boast latency of around 3-5 milliseconds.

‘Every simulator will have some subtle form of latency, whether that’s from the platform or tyre model behaviour,’ explains Yelloly. ‘When we had our current simulator installed, we did a lot of work on trying to minimise that and getting the car feel correct, in terms of how it slides, what type of slide it is and how fast the car or tyre recovers. Then, [F1] changed the style of the car to ground effect and a different tyre. So, we had to do a different step to make this closer again, which we’ve managed to do.’

Yelloly has driven multiple high-grade simulators, including the F1 rigs at Mercedes and Williams, and says the current Aston Martin one is at ‘a very good level’. The team has a new sim on the horizon, as it gradually equips its state-of-the-art new factory at Silverstone.

‘We have a great simulator team at Aston Martin that are constantly trying to improve things and looking for the next step forward, whether it’s immersion or how the simulator moves,’ says Yelloly. ‘There are so many different modelling, software and hardware tools that you can use to gain all these little feelings for the drivers. It’s cool and exciting to be a part of.’

How involved is the sim driver in a team’s season?

Although simulator drivers rarely attend F1 races – Yelloly says he’s only been two or three times – that doesn’t mean they are detached from the team’s progress throughout a campaign. It’s not simply a case of the driver being given parts to blindly test before the engineers take their feedback and squirrel away to make changes for the real car.

‘I feel quite involved, if I’m honest,’ says Yelloly. ‘I’m definitely not a face at the circuit. But, if I go in on the Monday, I will have usually worked the Friday, so I will know what items we were trying to get correct into qualifying. I’ll then have quite detailed reports when I’m back at the factory on how things went, driver comments, and how we went about trying to fix them from an engineering point of view.

‘Then, we will correlate the Saturday and Sunday, usually on the Monday, to make sure we are fully up to speed on what we are doing. And then we will try to progress to the next circuit…’

In the world of F1 where teams are constantly developing upgrades to improve performance, there is never a shortage of work on the simulator side. It is a vital process to validate the bright ideas from engineers before they are applied at the track.